by Letha Dawson Scanzoni

Introduction: In prior installments of the story behind the writing of All We’re Meant to Be,” I described the launching of the book project in late 1969 (Part 1) and left off at the end of Part 4 as Nancy Hardesty and I began our search for a publisher in the fall of 1970.

The book was not published, however, until 1974. But we never lost faith that it would be published, and after each rejection letter, we tried again with a different publisher. I want to tell that story in two sections, which I’m posting as Part 5 (this one) and Part 6 (the next one) of this series.

Hope and Confidence

In August, 1970, Nancy visited me for a few days as we continued our work on the book. By then, it was shaping up nicely. After she left, I wrote and thanked her for taking the time and bother to make the long trip.

I really felt the time together was extremely profitable, and once again I’m struck by the way we work so well together, our thoughts clicking together, new ideas or insights by one stimulating the other, and so on. Surely God is in this! I’m convinced of that without a doubt. And I have high hopes for the book, Nancy; I really think it’s going to be far better than either of us dreamed when we began—and that it will have a real ministry. I think the things we’ve thought through, talked through, and lived through are all going to give the book a depth and helpful function it couldn’t otherwise have. I can’t help but see God’s providential leading in all this—even the experiences of our lives that seemed painful or purposeless at the time. (Letha Dawson Scanzoni, letter to Nancy, August 12, 1970).

It was our sharing this belief that kept us going during the next two and a half years—even as publisher after publisher rejected our book proposal (a query letter describing the projected book, the outline, and some sample chapters) and later the actual manuscript itself.

Despair

Even so, we would be less than honest not to admit that there were also times of feeling dejected as time dragged on without any publisher’s being willing to offer a contract. In one letter, while saying, “we’ve got to hit the jackpot soon,” Nancy poured out her discouragement.

I couldn’t believe it last night as I looked through our stack of five different publishers, all topped with rejection letters. I guess I don’t feel depressed, just numb. And a little hurt and embarrassed because I’ve talked about the book for so long and people must think it’s awful that so many publishers have rejected it. I haven’t had the courage to mention the latest rejection to a soul around here. I almost did to Joan [Olson] the other day, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Well, God knows all that. When you’ve prayed for something for so long, do you ever get to the point where you just don’t bother anymore because he just doesn’t seem to care?” (Nancy Hardesty, letter to Letha, Dec. 18, 1972)

Life goes on

We were not just sitting around waiting as our book proposal (and later the manuscript) was making its rounds. Each of us was writing articles for various Christian periodicals and accepting speaking engagements which often involved travel, as well as carrying on all the other aspects of our daily lives.

For me, that meant not only family and household tasks but a heavy schedule related to teaching church-related classes and holding the weekly small group meetings of mostly university students in our family’s home. The “small” group that met Sunday evenings had now grown to 25 people, and I not only helped teach and lead the discussion but also made the refreshments each week and made sure the house was cleaned and ready for guests.

In one letter to Nancy I told her how I yearned to have just one Sunday evening off. During 1970-1971, I was also keeping up my own heavy load of university studies, pedaling my bicycle back and fourth between home and classes (three miles each way).

Often I shared with her stories about my everyday family life, as in this paragraph:

Steve and Dave are off from school all week this week (because the school system ran low on funds so cut off 3 days from the school year—which means the teachers lose 3 days’ pay plus what they lost from Nixon’s freeze), so I have more interruptions than usual and an extra meal to prepare in the middle of the day. But I am trying to take time with them and not be too preoccupied, even though I have started my new project. This morning I helped Dave get started on a craft set (wood plaque kit) we got him for his birthday. Steve is busy writing an English report on flying saucers and the project fascinates him; then the afternoons he spends at the computing center [at IU]. Seems to be a real scholar and says his work is his fun! John is still busy at IU every day with the female role/fertility project, and soon all the data will be ready for analyzing—which is when it becomes more fun after all the tedious work of coding. (Sidelight: that word “fertility” triggered a thought. A few weeks ago we were riding past the campus area when David started saying something about “the fertility houses” and we at first didn’t know what he was talking about; then we saw what he meant—the fraternity houses. He just got his words mixed up, but John laughed and said it might not be too far off!) (Letha Dawson Scanzoni, letter to Nancy, Nov. 23, 1971)

One afternoon in 1970, I began a letter to Nancy with the opening paragraph written in Latin. I went on:

I guess from the above you can easily guess what I’ve been working on this afternoon. I thought of writing the whole letter in Latin, but decided you probably wouldn’t especially appreciate that!

It’s been a busy day. I got up at five to review for a midterm exam at 8:30 a.m., then another class, then home to work on Latin, then an appointment at David’s school for a conference with his teacher (twice a year they do this instead of report cards), then back home to do a washing, more Latin, and this letter. And really I don’t even feel tired. God is certainly granting strength and peace; I couldn’t explain it otherwise. (Letha Dawson Scanzoni, letter to Nancy, November 5, 1970).

Shortly before writing that letter I had fulfilled a speaking engagement in California after which a Regal Books editor approached me and asked if I would like to write a book on sex education in the Christian home. And so in this same Nov. 5 letter to Nancy, I had said, “Yes, as plans now stand, I should be finished with my university work sometime next summer. Probably I will take the Regal Press contract too and begin work on that either in the fall or concurrently with our other book.”

Nancy, for her part, was just as busy as I during those years of waiting for a publisher to say yes. She was taking seminary courses, writing articles, teaching English and writing classes full time, serving as chair of the division of language and literature (which, as she explained in an April 19, 1971 letter, “also means membership on the Administrative Affairs Committee which essentially runs the college) and faithfully fulfilling the duties of her part-time sportswriting job for the college. In a 1971 letter she wrote:

It’s Sunday evening, 8:30, and I have my sports stories done (two very dismal losses at away games this week—I just figured that the government figures I spent $26.76 driving this week! [Gasoline was 36 cents a gallon then]). I also have 65 term papers read, which is all I can find at the moment. I don’t know where the others are and I can’t say I care. Actually they were rather interesting. I got one on authority in the family and when she turned it in the girl said she was scared—and I know why. She came to all the traditional answers. I told her she could have done more solid biblical research, but I admitted that if she had read six or eight more commentaries, she probably would have come to the same conclusions. Our position isn’t too widespread. (Nancy Hardesty, letter to Letha, January 17, 1971)

Or again on another Sunday evening in 1972:

I’ve been working since I came home from church at 12:30 and just finished grading all the papers and writing my two sports’ releases. I also graded papers before church and last night and yesterday morning. I should be putting together a test at the moment but I’ve wanted to write to you. Work takes so much time and it frustrates me. (Nancy Hardesty, letter to Letha, Oct. 8, 1972, 9 p.m.)

Her part-time job as sportswriter had attracted attention outside Trinity College where she taught. During the first week of February 1971, the Chicago Tribune published an article by Mike Conklin describing Nancy as a rarity in the sports world—a female sports publicist. Calling her “Miss Hardesty” throughout, the article pointed out how seriously she took the job, working at it almost full time and becoming one of the school’s most devoted fans, attending all the home basketball games and many on the road. In the previous fall, the article said, she was the “only person to attend every cross-country meet.” The article pointed out problems she had encountered at first. “The wire services didn’t take me seriously when I called in results. Some of the newspaper men would tease me,” Nancy told the Tribune reporter.

The article mentioned the book she and I were writing, which at the time we titled The Christian Woman’s Liberation, and concluded that Nancy “probably could add a chapter on her part-time job.” (A photocopy of the article, without a date, was included with Nancy’s letter to me dated February 4, 1971.)

Travel

Not only did we each sometimes travel for speaking engagements during this time, but in 1972 Nancy spent much of July on a tour of the Scandinavian countries. Before she left, she sent me a schedule and an American Express brochure that listed the places where mail could reach her throughout her travels. We carried on our copious correspondence as usual, although a bit less frequently and with much shorter letters because we tried to write them on those pale blue tissue-thin all-in-one airmail letter forms to save on postage costs.

Nancy’s eagerly anticipated letters from Scandinavia brought more that business discussions about getting the book published; they offered me a vicarious visit to Norway, Sweden, and Denmark through her colorful descriptions.

The publishing saga continues

From late 1970 through 1973, we kept shuffling names of publishers around like a deck of cards. Which one would we try next? Or should we change the order around again and try this or that one instead?

Along the way, two publishers (the Holman division of Lippincott, and Creation House) had heard about our project through connections with Nancy and had approached us. But neither of them accepted the book after they looked at the outline, purpose, and sample chapters. (Russell Hitt, Nancy’s colleague at Eternity magazine years earlier, was now also serving as editor for Holman/Lippincott, so had expressed interest in seeing our book proposal; and Creation House was the publisher of the 1972 Clouse, Linder, and Pierard book, The Cross and the Flag, in which Nancy had been invited to write a chapter titled, “Women and Evangelical Christianity.” )

All of the other publishers were those we ourselves contacted after looking up names in The Writer’s Market or The Writer magazine. We never thought about contacting a literary agent because, at that time, unlike now, publishers were willing to consider unsolicited manuscripts. Nancy and I took turns querying various publishers.

Holt, Rinehart and Winston—and a new friend

One of the first publishers we approached was Holt, Rinehart and Winston. As the 1971 spring semester began at Indiana University, I was talking with my assigned advisor in the IU Religious Studies Department, Dr. William L. Miller, who was one of several professors who had made it possible for me to write large sections of our book as honors projects for independent study credit. Dr. Miller asked me how the book was coming and who we planned to publish with.

As I described this meeting to Nancy afterwards, I wrote: “When I mentioned we were thinking of Holt, Rinehart and Winston as first choice this time, his eyes lit up and he said, ‘Well, we’ve had lots of contact with them. Joe Cunneen, their religion editor is really great.’”

I said I knew that Dr. William F. May, our department chair, had published with Holt and asked if he were pleased. Dr. Miller said he couldn’t have been more pleased with the editor and told me more about Mr. Cunneen, a Roman Catholic who was also editor of the prestigious religious journal, Cross Currents.

Encouraged and excited, I told Nancy:

[Dr. Miller] said with our topic (the religious angle on the woman issue) the book should sell without question. Anyway, he suggested we write to Mr. Cunneen and tell him he [the advisor] suggested him. So that gives us a little personal touch. (Letha Dawson Scanzoni, letter to Nancy, Feb. 3, 1971).

And so I wrote to Joseph Cunneen and sent him our proposal package. Although he said that Holt could not agree to publish the book (partly because they had recently published Elsie Gibson’s When the Minister Is a Woman and had been deeply disappointed by poor sales), Mr. Cunneen nevertheless took the time to write us a long evaluation of our project and its marketing prospects. He offered to give us further advice any time that we wanted to contact him in the future.

I think one reason he was so helpful and understanding was that his wife, Sally Cunneen, had published a book about women’s questions and concerns in the Catholic Church a few years earlier (Sex: Female; Religion: Catholic, Holt, 1968). He had told us about that when we first contacted him, indicating that he was aware of our concerns about faith and feminism in a personal as well as scholarly way.

When I sent Joseph Cunneen’s gentle rejection letter on to Nancy, along with my own letter to her, I talked about the publishing industry in a way that sounds as though it were written today!

I’m wondering now if it would be best for us to continue as planned with another general publisher, or do you think we should contact Floyd Thatcher at Word? Who will push it more is an important consideration—the book has to reach the audience we believe (and Mr. Cunneen believes) is out there somewhere!

There is also the problem that the publishing business in general is having a hard time right now. The faculty wife that I ate lunch with on Friday told me her husband’s publisher (Appleton) just laid off 20 members of the editorial staff, including her husband’s editor of the book he has in production. When this happened, my friend then called her sister who works for a literary agent in New York and she told her this is happening all over in the publishing business—that with the economic slump in general there seems to be panic in the book, magazine, and newspaper industries.

Also, Mr. Cunneen’s comments made me more aware of what rare specimens you and I are! In a sense, we are writing for evangelical and conservative Christians, as he surmised (and they especially need the message, as we know!)—and there’s no getting around the fact that we’re taking a conservative approach to the Bible that is somewhat out of vogue in religious circles today; from our writing one would gather we don’t know higher criticism exists—which would cut out the possibility of our being sponsored by some large, major denomination as he suggested. However, on the other hand, what conservatives would claim us either? Other than Word, I can’t even think of a “broadminded” religious publisher who would want us. Eerdmans probably wouldn’t push it. . . .

But I’m not discouraged. I still have great faith in our book and am sure we’ll find a publisher. But we must be praying that it will be the right publisher. Mr. Cunneen’s assessment should be helpful in thinking this over further, but time is passing quickly, and I’d like to send off the manuscript right away again. So please let me know as quickly as possible what you think. Where shall we send it again? (Letha Dawson Scanzoni, letter to Nancy, March 23, 1971)

Nancy replied in a letter dated March 29, 1971. “In some ways, I would still like try Harpers but that’s more sentiment than sense,” she said. At the same time, she believed that Word would probably advertise it more. “I would say, send it to one of those two—the choice is up to you. I don’t really care which.” She added that God would put it where God wanted it but that it might just take us a while to find exactly where that was. “I’ll be praying,” she assured me.

I wrote back:

I plan to retype the covering letter tomorrow and send our stuff off again—and I’ll take your first suggestion and try Harpers. Why not? We said we wanted to try the New York publishers first, so let’s do. Our only problem is the time lapse—waiting 6 or 8 weeks each time. I hope we know something definite by summer so that we can really dig into the project earnestly. (Letha Dawson Scanzoni, letter to Nancy, March 31, 1971)

“Ladies in Waiting”—for Harper!

At the beginning of April 1971, then, we sent the outline, sample chapters, and other information about our book to Harper & Row. By October 1971, they had given us the go-ahead to send them the entire manuscript for consideration, which we did. Our hopes were high.

Then we heard nothing further from them until March, 1972 when they wrote wanting major changes and asked us to reorganize the book drastically and condense it. They especially wanted us to delete much of the scholarly section about gender issues in the Bible, saying such information was available elsewhere, and told us to concentrate on the later sections because they felt those more practical chapters would be of more interest to women.

Nancy and I talked by phone on March 7, 1972. We were totally surprised at the Harper request for what would amount to a major rewrite. As Nancy and I brainstormed about it by phone and letter, Nancy suggested we might even discuss the possibility of writing two separate books: a practical one which seemed to interest the Harper editors and marketing people most and then a separate scholarly book. I agreed that this might be an option if no publisher wanted it whole—the way we planned it. “We just can’t let all that work go to waste!” I wrote to Nancy on March 9, 1972.

She replied:

If we wrote him [the Harper editor who had written to us] immediately, do you think we would have a reply by the time we get together the week of March 27? Yes, and the world will turn to ice cream and they’ll declare my birthday a national holiday! (Nancy Hardesty, letter to Letha, March 14, 1972)

Nancy said she would write to Harper. At the same time, she said she might approach Joseph Cunneen again (a year after we had first contacted him at Holt)—this time just for his opinion and advice as he had offered to provide at any time. And so she send off some questions to him about Harper’s suggested changes at the same time as she wrote to Harper. As before, Mr. Cunneen replied graciously and helpfully, patiently answering our questions, and even seemed willing to leave the door open to possible consideration of our book again—although he didn’t feel he would be able to promote it to the extent it would need.

Responding to the Harper & Row rewrite request

In part of her reply to Mr. H. Davis Yeuell (then editor at Harper), Nancy addressed his comments about our chapters on biblical scholarship. Nancy asked, “Just how much deletion do you intend?” She continued:

We have written a scholarly book and we would like to keep it that way. Too often women’s intelligence has been insulted by homey, practical books which do not really grapple with the issues. While we wish to be practically helpful in the final chapters of the book, we feel that among Christians this can only be done after one has made a strong biblical base against the stereotypes which have kept women in subjection. As one woman commented at a social gathering recently, “Why don’t Christian books about women treat some of these issues in depth? If they expect us to be thinking women, why don’t they give us some documentation?” In researching our book, we were often disappointed in other books on the subject because they gave us no sources for their information, no citations as to where we could dig deeper. We don’t want to do our readers this disservice.

And perhaps this leads to a related point which needs clarification. While we are women writing about “woman,” we have not intended to write a “woman’s” book. We hope to speak directly and personally to biblical scholars, pastors, teachers—as well as to laymen and laywomen. We feel that the women who read McCall’s are basically intelligent enough and interested in delving into sophisticated biblical exegesis. While the manuscript can certainly be edited for further clarity and conciseness throughout, we would hate to simply delete the basic biblical argumentation. (Nancy Hardesty, letter to H. Davis Yeuell at Harper & Row, March 14, 1972)

Mr. Yeuell answered her by phone on April 12, 1972 and told her that ideally the book would be 120 pages printed or perhaps 160 at most. Cost was the issue because more pages would mean a book would have to be sold for a higher price(say, $5.95 hardback), which would cut down on sales. Nancy described the call further.

I tried to question him about his feelings about the extent of our scholarship and he replied that he was ambivalent on the issue, that at “one time” he really did see it as a “woman’s book.” And he noted that “If the book is weighted toward scholarly intent, then at the present time this would restrict sales.” He is not opposed to scholarly apparatus in a book—but of course that costs money (a key theme in the conversation!) (Nancy Hardesty, letter to Letha Dawson Scanzoni, April 12, 1972)

He told Nancy he couldn’t give definite answers about publishing it but would reply to both of us early the following week.

On April 24, 1972, after an entire year had gone by since we had first sent the query to Harper & Row and been given the go ahead, we each received a rejection letter. I received the returned 350-page manuscript four days later.

“Well, now we know, don’t we?, “ Nancy wrote to me. “I’m angry that they took so long, but really I’m very relieved that finally they have just said No and stopped beating around the bush.” She went on:

I disagree with him [Mr. Yeuell], of course, that the material is available to most scholars—of course, everything is “available” or we wouldn’t have been able to dig it out—though in places our thought on the Bible is original. Yet “available” to be dug out and pulled together logically in one place are two different things. In this regard I think our book does a very valuable service. But maybe the pastors they would reach wouldn’t want this kind of serious, broad material. Maybe it is too technical in places.

What I wish is that before we wrote the book, someone would have been helpful enough to have told us what size is realistic. Then we could have tailored it to fit at that point. (Nancy Hardesty, letter to Letha, April 26, 1972).

My feelings were similar to Nancy’s. When the returned manuscript arrived April 28, I immediately wrote to Nancy: “I might call you tonight or tomorrow to see what you think we should do with it next!” I suggested we try Holt one more time, adding, “I really like Cunneen and his attitude. What a contrast.”

I interacted, too, with Nancy’s reaction to Harper’s rejection letter.

I agree with you that Harper’s point about our scholarly material’s being “available” is far-fetched. By that sort of reasoning nobody would have to write any scholarly books any more—since anybody could dig for hours searching the world over for the sources such books cite! Also, you’re right—the way we put it together and our interpretations are unique, and many of our ideas are quite original. (Letha Dawson Scanzoni, letter to Nancy Hardesty, April 28, 1972)

(Another aside here, as something struck me as I am looking through all these letters forty years later. Harper’s argument that the biblical scholarship we had discovered and used in our research was “readily available” reminds me of a time many years ago when a woman asked me what kind of work I did. When I said that I was a writer and wrote nonfiction, she asked what writers did—how they knew what to write about. I told her about having ideas and questions about a topic and then researching that topic in various ways to gain new understanding. Part of that involves going to a library and reading books and articles on different aspects of the topic, and then putting everything together with one’s own ideas, theories, and explanations to create an altogether new book or article. It would then provide additional information and new ways of looking at the subject. But her mind was still stuck back at my remarks about library research. Looking puzzled, she said, “But if it is already there in all those library books, I don’t understand why you have to write about it, too.”)

Needing guidance

After Harper’s having kept our manuscript out of circulation so long, we were back to square one in seeking a publisher. But we decided to try Cunneen again, this time with the complete manuscript on the outside chance that Holt might change its mind about publishing the book.

In my April 28, 1972 letter to Nancy, I also acknowledged that our female socialization had no doubt kept us from being more assertive. Joseph Cunneen had alluded to that in his response to Nancy’s earlier letter asking his advice in view of Harper’s demands for what felt to us like an amputation of a section we viewed as essential and then wanting the book reconstituted into something that was not our intent.

I also resonated with what Nancy had said about our not having received manuscript-development guidance from Harper during the year they took to make up their minds. I wrote:

. . .[R]emember one reason we chose Harper was that The Writer market list included their statement that they are a publisher which likes to work with the author from start to finish. Yet they never used that partnership-team approach with us at all. In many ways, they acted much like Revell did with my first book. Which makes me realize I should have learned some lessons by now! Cunneen’s right; we were too retiring. We acted like women! Both of us were so busy with other projects and responsibilities—that was part of the problem I think. But we’ll know better next time. (Letha Dawson Scanzoni, letter to Nancy Hardesty, April 28, 1972)

So I sent the manuscript to Holt. And once again, as when we had approached Joseph Cunneen with the book idea in March 1971, he was encouraging. But also once again, he had to give us the bad news that Holt was still not willing to take a chance on the book.

Yet he took time to provide us with more wise advice, including pointing out an inconsistency in style that sometimes showed up in some of Nancy’s and my writing as we switched from intellectual discourse to chattiness. And he suggested we create interest in the book in advance of publication by first writing up some of the chapters as magazine articles for a wide range of religious publications (conservative, middle-of-the-road, and liberal) and also for secular women’s magazines.

Nancy was still in Scandinavia when I received that letter from Mr. Cunneen. As I summed up for her all that he had said in it, including his ideas of other possible publishers and his suggestion that we cut only 10% or so (far less than Harper wanted deleted), I added these words: “He appreciates our thorough research much more than anyone else has.” (Letha Dawson Scanzoni, letter to Nancy, dated July 18, 1972)

Nancy replied from Copenhagen, Denmark, in crisp, pithy, abbreviated sentences to save space on the air mail stationery:

About Holt—I’m not surprised but I am sorry. I wish we could stop worrying about it. But we can’t. Of his suggestions on next try, I favor Fortress—they promote best, publish good books. Eerdmans is second—good books but don’t sell. It’s too long and serious I fear for Word. Friendship book [another book we had hoped to write] is more their bag. I still wish we could get secular publisher but seems hopeless. (Nancy Hardesty, letter to Letha, July 25, 1972)

Is Anybody interested?

In the next month or two, we sent letters and descriptive material to several publishers all at once, rather than one at a time, and told them what we were doing. We said we just wanted to find out if any of them might be interested in looking at our manuscript.

Fortress chided us for that approach and said they would want exclusive rights to examine either the proposal or the manuscript for at least six weeks and would want our assurance that no other presses would be looking at it at the same time. They pointed out that this was standard publishing procedure.

We had followed that standard, of course, with all our previous attempts to find a publisher; but now time was rushing by, and we had had already had the experience of Harper’s having kept the manuscript out of circulation for an entire year and then rejecting it.

Fortress also felt that we shouldn’t base our approach on our interpretation of the Bible because the Bible could be used to prove anything and that many Christians, “both more conservative and more liberal,” would likely come to different conclusions than ours. The Fortress editor at the time, Norman A. Hjelm, wrote, “Accordingly, it would seem to me that the value of your book would rest in later chapters rather than an attempt to make either a biblical or theological case for your point of view.” (From Norman Hjelm, Letter to Nancy Hardesty. August 29, 1972.)

Once again, we were being asked to concentrate on the practical parts of the book in which we discussed marriage and singleness, childbearing and childrearing, women in the marketplace and in church leadership positions, and so on—all good topics, of course, but without the biblical foundation that we believed was crucial for the evangelical audience we hoped to reach.

Feeling alone

Not only were publishers rejecting our ideas, but we felt very alone. Finding other Christians who supported our view of gender equality seemed almost impossible within the conservative evangelical circles we identified with during the early 1970s. The pastor of my church preached on male headship and female subordination, and the women in the church seemed to agree with him. In the college Sunday school classes which I co-led with John and another man, I was told by this man that my teaching women that a Christian marriage could be egalitarian would make wives discontent and thus hurt marriages where the wife had been happily fulfilled in her subordinate role until I came along with these feminist ideas.

My pastor once said in a sermon that he had just figured out why wives seemed so thrilled about going out for a restaurant dinner. “It gives them a chance to be waited on!” he exclaimed, proud of the brilliant insight that had just struck him. It apparently never occurred to him that Jesus talked about serving others, even to the point of washing the feet of his disciples, and that perhaps husbands could “wait on” wives, just as they were expected to “wait on” husbands.

After I gave a talk at Trinity College in May, 1970, Nancy reported that it had been “very good for the campus,” but went on to tell me some of the student reactions:

I can’t say though that it was received with equanimity. As in most areas, the men are the more vocal and as one admitted, they were all very threatened by what you had to say. So the criticisms were often loud and vehement. Since there is not too much understanding of the Scripture involved, some had trouble following your arguments. They didn’t know the scriptures to which you were alluding, so they got lost. But some who got your point, did feel that you were threatening the authority of Scripture. . . .

But of course there were some gratuitous observations: “Children are enough for the women in my life. . . .” I gave a three-minute rebuttal about how long does it take to raise kids against the normal length of a woman’s lifetime. . . .All in all it was very much fun and I think they have begun thinking. Next fall should be even wilder. . . .

Incidentally, one other reaction to your talk from a guy who very obviously read his newspaper as a protest throughout it, was that although he thoroughly disagreed with the entire women’s liberation movement, he was glad that with all the serious problems around there was one cause that was sort of a farce, comic relief and all that. Glad he didn’t tell me that or I would have slapped him just to show how serious we are! (Nancy Hardesty, letter to Letha, May 17, 1970)

Nancy frequently ran into such discussions in some of the seminary courses she was taking. She said one professor “brought up a point about creation and proceeded to say that women were subordinate and thus were assigned less desirable tasks: e.g. he would rather be lecturing a class in theology than washing diapers, etc.”

He said that women were equal in personhood, but different in role—the same old garbage. So I raised my hand and we were into it. Out of 50 students only one guy really tried to help me out. The girls agreed with him [the professor]

My opening statement was something to the effect that to say women are equal yet subordinate is a plain contradiction by any use of the English language (yesterday morning I looked them up and in two dictionaries—in no way can they be used together, they directly contradict each other in all meanings). Anyway, one girl immediately said that she couldn’t see my point—that one applied spiritually and the other on earth! But we were talking about creation and he had agreed we were created equal. (Nancy Hardesty, letter to Letha, Jan. 10, 1971)

She went on to write more about the class discussion and then said:

Letha, I get scared! I can hold up my side in an argument like that but afterward I feel so drained and lonely. I’m glad I’m in this with you, because I sometimes think we’re the only Christians in the world who think women are in God’s image. Somehow I really don’t get upset about what people say about me in print, but in person it’s a different matter. When everyone else seems to be so certain of having “God’s truth,” I find it emotionally taxing to maintain that I too have the mind of Christ. But in praying about this on Friday, I did get some peace. (Nancy Hardesty, letter to Letha, Jan. 10, 1971)

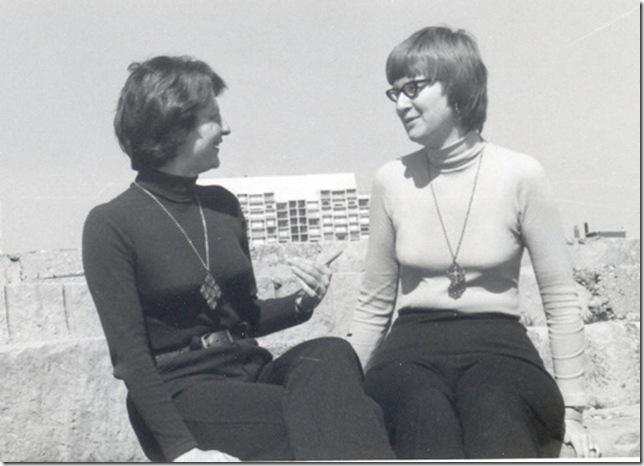

Nancy (l) and Letha (r) circa 1973.

Nancy (l) and Letha (r) circa 1973.

Where were the other women like us?

In 1972, I too began voicing such feelings of standing alone with so few people who agreed with us, as I wondered at one point whether maybe we should just go ahead and make the drastic changes the publishers seemed to want.

In a letter to Nancy, I referred again to our biblical scholarship and asked,“Can we really convince the theological world (mostly men) with what we feel is a solid apologetics-type thrust? Will they even listen to such a view? My experience with my pastor and yours with the theology classes makes me wonder, if not actually despair.”

I continued with some ideas of how we might even totally rewrite the book if necessary. I continued:

I know in some ways that sounds like a compromise or becoming untrue to our ideals. Yet, Nancy, I’m beginning to wonder. We wrote that book having in mind women “like us.” I’m beginning to wonder if there are many women like us! Actually, we know there aren’t—otherwise we wouldn’t have found it so difficult to find those of similar intellectual, spiritual, and personal interests over the years. That loneliness, that yearning to find other women who think as we do has been a problem over the years. (That’s why it’s so great that we found each other!) We tried to write a book which was basically evangelical (yet tried to be a bit broader than that), feminist, and intellectual. Maybe we just aimed between markets. Eerdmans would be the closest perhaps to a publisher that tries some of these types of approaches. (Letha Dawson Scanzoni, letter to Nancy, July 25, 1972)

But Eerdmans turned us down, too.

And Nancy’s friend Russ Hitt of Lipponcott had also lent credence to what we didn’t want to face—that maybe it was true there weren’t many women “like us” and thus our book wouldn’t find an audience. Russ Hitt had written that while we might not agree on the “traditional women’s market,” he could assure us there was one. He told Nancy, “But you are most unusual among my wide acquaintances. You have a grasp of theology that is not characteristic of many women I meet and attempt to talk to in theological terms. This may be changing, but not in a revolutionary way yet.” (Russell Hitt, letter to Nancy Hardesty, January 4, 1972)

Finally, Good News!

Then on August 27, 1972, in response to that query we had sent out to numerous publishers all at once to see if any of them had any interest at all in our project, we received a letter from Floyd Thatcher, the executive editor at Word Books in Waco, Texas. He wrote:

I am intrigued by your letter of August 10 and the accompanying descriptive material. Word Books is ready for anything as far as the exploration of ideas in today’s society. For this reason, I most definitely would like to see this entire manuscript and react to it. Please send it along to my attention and we’ll try to get into it immediately, so as to give you an early response. (Floyd Thatcher, letter to Nancy, August 27, 1972)

At last, perhaps we were on our way to publication! But I’ll save the rest of the story for the next chapter.

Copyright © 2011 by Letha Dawson Scanzoni

The rest of the day we would spend walking and driving around Asheville and visiting the city’s fascinating shops, looking at books, jewelry, scarves and shawls, art, crafts, and more. Or we’d stop and listen to street musicians. Then we’d take a break at a coffee or pastry shop in the afternoon, such as when I snapped this photo (left) of Nancy in front of some Christmas decorations in 2007.

The rest of the day we would spend walking and driving around Asheville and visiting the city’s fascinating shops, looking at books, jewelry, scarves and shawls, art, crafts, and more. Or we’d stop and listen to street musicians. Then we’d take a break at a coffee or pastry shop in the afternoon, such as when I snapped this photo (left) of Nancy in front of some Christmas decorations in 2007. her to strike a comic pose in front of a humorous poster we found inside one of the coffee-and-pastry shops. I joked that we could have used that for her singles chapter. (See photo on right.) She had a marvelous sense of humor and we had lots of laughs together over the years. This sign provided one of those laughs.

her to strike a comic pose in front of a humorous poster we found inside one of the coffee-and-pastry shops. I joked that we could have used that for her singles chapter. (See photo on right.) She had a marvelous sense of humor and we had lots of laughs together over the years. This sign provided one of those laughs. the rocking chairs on the front porch, conversing and watching the “real”guests coming and going.

the rocking chairs on the front porch, conversing and watching the “real”guests coming and going.

Nancy (l) and Letha (r) circa 1973.

Nancy (l) and Letha (r) circa 1973.