by Letha Dawson Scanzoni

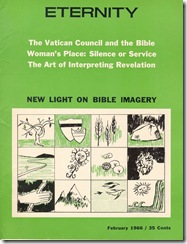

Numerous scholars of feminist history have referred to my February 1966 article for Eternity Magazine, citing it as one of the first evangelical or biblical feminist articles to be published during the “second wave” feminist movement that began in the 1960s. Because of this interest, I want to correct some misinformation that has been circulated, as well as tell how the article came to be written and changes that were made in the editing before its publication.

This post, then, tells the story behind “Woman’s Place: Silence or Service” as I promised on this website in my reprint of the original manuscript.

First, some corrections.

Setting the Record Straight

From reading the brief author information blurb that was placed with the article as it appeared in print, various scholarly books and articles began making assumptions about my background that were way off the mark. Here is what I think happened.

Misunderstandings about the biographical information. I had not included any author bio information when I had sent in my article, assuming that the editors knew enough about me from some prior contacts with them. I thought they would mention simply that I was a free-lance writer who had authored one book published in 1964, with another in press for 1966 publication. (I learned not to take such matters for granted even when I’m known to editors!)

This is the brief author-identification statement that appeared with my article as printed in the magazine:

“The author and her husband are engaged in Inter-Varsity work in Indiana University (Bloomington) where he is also professor of sociology.”

Technically, the information printed was not untrue. I was married to a professor of sociology at IU, and we both worked closely with college students through a local church and unofficially with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship (IVCF) in the sense of sometimes speaking at their meetings and often informally inviting university students (some of whom belonged to IVCF) to our home for Sunday evening Bible study, discussions, and refreshments. I had mentioned this, along with a request for extra copies of Eternity magazine to distribute to these students, when I wrote the cover letter that had accompanied my article. I had addressed it to William J. Petersen, a wonderful person and executive editor at Eternity who was willing to stick his neck out to publish an article that was considered quite controversial at the time. But someone on staff had condensed this information from the letter and had composed the brief author-identification blurb above.

As a result, various scholars, without contacting me for fact checking, began expanding on who or what they thought I must be. One assumed that I, not John, must be the professor and implied that the mention of him and not me was an example of sexism. Fortunately, I was asked to review that dissertation or book manuscript in advance and was able to correct it.

Another scholar interpreted the blub to mean I was an InterVarsity staff member, which I have never been. (In fact, before my second article (this one on egalitarian marriage) was published two years later, I had written to Bill Petersen with this request:

. . . I hope this request isn’t out of order, but could you please mention my books, Youth Looks at Love and Why Am I Here? Where Am I Going (both Revell) in the author-information paragraph? I’d appreciate that. Also, please don’t list me as an Inter-Varsity worker—mainly for the sake of accuracy, but also because I wouldn’t want I.V. to become innocently involved in any criticism that may arise if anyone feels any of my articles are too provocative. (Excerpted from my Oct. 18, 1967 correspondence.)

The other misidentification scholars have applied to me is that I was a graduate student in sociology at Indiana University when I wrote “Women’s Place: Silence or Service?” I was not. In fact, I was (and still am) an independent scholar, and I was not enrolled as a student of any kind at the time. By then, I had completed three years of higher education several years earlier (three semesters at the Eastman School of Music, part of the University of Rochester, NY, and three semesters in the sacred music department of Moody Bible Institute in Chicago); but like so many women following the societal expectations and prescriptions of the 1950s, I had married young, even though it meant postponing the completion of a college degree until later.

At the time that I wrote the Eternity articles, I was working from home as a free lance writer and mother of two young boys. Only later did I complete my university education with a Phi Beta Kappa degree from Indiana University in 1972, having majored in religious studies and having taken as many sociology courses as possible. By then, I had already written three books and was at work on two others (Sex Is a Parent Affair and All We’re Meant to Be) at the same time that I was completing my undergraduate degree. Some of my professors encouraged me to do research on material for All We’re Meant to Be as independent honors courses. I was by then in my mid 30s.

As I wrote in correspondence with Dr. Sue Horner three decades later in connection with her research on biblical feminism for her dissertation and a possible book:

[So many people] have over the years attributed to me degrees and titles that I don’t have; and in spite of my repeated attempts to get this corrected, the practice seems to continue. For the record, I do not have a doctorate and am not officially a sociologist. I am, and have always been, an independent scholar and writer who specializes in the interface between sociology and religion. So you could accurately say I am a sociology writer where such an identity fits the context. [This would be comparable to a science writer or medical writer or professional writer in some other specialized field.] After having written numerous books of my own, I was asked by McGraw-Hill to coauthor a sociology text with John [at a time when McGraw-Hill was pairing professional writers with academics to produce college textbooks]. . . .Thus, I kept up in the field of sociology. (Letha Scanzoni, from a personal letter to Sue Horner, February 2, 2002).

I can also, of course, be identified as a religion writer and editor.

Is It True that I Did not Believe Women Should be Pastors?

In their entry on “ Euro-American Evangelical Feminism” in the Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America, Reta Halteman Finger and S.Sue Horner referred to my 1966 Eternity article as “one of the earliest evangelical feminist articles.” But they went on to indicate that some of my views appeared tentative and concluded that I was hesitant to express an opinion that women could be pastors. They wrote:

Scanzoni identified the inconsistencies and often absurdities associated with teaching on women’s submission. She pointed out that there were numerous examples within the church of women teaching and leading, as well as broadening employment opportunities for women. However, at this early point of feminist awareness she also made the disclaimer that “this article is not intended as an impassioned clamor for women’s rights or female pastors!” ( R.H. Finger and S.S.Horner in Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America, edited by Rosemary Skinner Keller and Rosemary Radford Ruether; Marie Cantlon, associate editor. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2006, Vol. 1, p. 469.)

They went on to say that my tone had changed by 1973 when I wrote “The Feminists and the Bible” for Christianity Today.

Both Reta and Sue are friends of mine and sister members of EEWC-CFT but they had not asked me about my views on women’s ordination before publishing their encyclopedia entry. I wish they had. What they didn’t know was that the Eternity editors had toned down my points about women in ministry by cutting out significant sentences before publishing “Women’s Place: Silence or Service,” and I was not consulted about these edits before the article appeared in print.

If you were to compare the published version side by side with my original manuscript, you would find several sentences removed from the paragraph that begins “This was the first of many such contradictions I’ve observed.” (It’s the paragraph right above the heading, “Other Arguments” in the published version):

Inconsistency coupled with inflexibility produces many problems — one of which is that women feel forced to serve the Lord with guilt instead of gladness. A single woman serving Christ in a remote section of Japan described worship services she and her co-worker held for the little band of believers. “I don’t really believe in woman preachers,” she said apologetically. Then, with a sigh, added, “But what else can we do?” Such Christian servants find little help in trite statements such as, “If men were doing their part, you wouldn’t face this dilemma.” The Holy Spirit has distributed His spiritual gifts to these women, and He is using them. Is it God’s intention that they must feel they are sinning by serving?

The section beginning, “a single woman” was cut when the article was published, and the last sentence was made to apply to women in a general way rather than to these particular women who were leading a congregation and preaching to a small congregation as part of their mission. It is possible that this illustration as well as a few other sentences here and there (amazingly few overall!) were cut from my original article because of space limitations.

But unfortunately, one part that was cut was the entire section right before the statement cited by Sue Horner and Reta Finger (“This article is not intended as an impassioned clamor for women’s rights or female pastors!”).

This is what I originally wrote right before that sentence:

Other arguments merely skirt the issue. Does the fact that Paul omits women from his list of resurrection witnesses negate the truth that the risen Savior called Mary Magdalene by name, telling her to broadcast the good news? Does the fact that the incarnation occurred in a male body prove anything about woman’s place? (One could just as easily argue that “God sent forth his Son, made of a woman.”) Then there’s the old argument about female cult founders, proving (said one Bible scholar) that “women are easily swayed and unsafe repositories of doctrine.” However, false religious groups have also had male founders and leaders; and seminaries which have veered from loyalty to God’s Word are for the most part staffed by men. Some evangelicals feel the matter is settled once for all by asserting that it is the liberal wing of Protestantism that rejects biblical authority and therefore ordains women pastors and elders. Such a statement ignores the phenomenon that Pentecostal and Holiness groups — groups which can hardly be accused of denying the Bible’s inspiration — for years have given women places of leadership.

But everything in that paragraph after “(One could just as easily argue that “God Sent forth his Son, made of a woman.)” was cut out.

Thus, as published in the magazine, the sentence about my article’s not being a clamor for women’s rights or women preachers was left to stand all by itself without the context. That’s why the point of my intended meaning that this article was not primarily focused on the issue of women’s ordination struck some as implying that I probably didn’t believe in it!

The Times in Which I Was Writing

There are several reasons why I think the editors removed the section before that sentence, knowing the emotional climate of the times in which this was being published. I think they didn’t want me to come across as being “too strong.” Large numbers of people in the U.S. (not just church people) were already upset about the idea of women’s rights. There had been quite an uproar over the 1963 publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and the movement it had engendered during the mid-1960s.

And even as it was, reactions to “Woman’s Place: Silence or Service?” were vehement. The first letter to the editors that appeared in print after the article’s publication, said, “Mrs. Scanzoni’s article is a perfect example of why a woman is admonished to be silent in the church.”

The editors rightly sensed that I had wanted to approach the topic of women in the church by asking a series of questions to stimulate people to think and to question whether (or why) any kind of service should be off limits to women. It was a way of raising consciousness, although I don’t think we would have used that word.

It was common in many churches at the time not only to believe that women should not preach and lead congregations but also that they should not be participants in church governance—one reason I used the question of a woman’s being church treasurer.

Much of this may seem utterly absurd now in the 21st century, but at the time I was writing, many congregations the world over would not even permit a woman to take up the church offering. The controversial British bishop, John A.T. Robinson, wrote of having returned from speaking at a conference in Sweden in 1964 and receiving a letter from a woman who wrote: “My friends point out that a half-witted man can, for a small instance, take round a collecting bag, but that the most brilliant woman must have no part nor lot in the Church. Even the mild suggestion of making them Lay Readers has met with fanatical resistance.” She went on to say her personal faith was strong but wondered what she could tell her friends. “Is there any way of making them see that our God does regard all souls of equal value in spite of the Church, which certainly does not?” she asked. (Quoted in John A.T. Robinson, The New Reformation? SCM Press in the U.K and Westminster Press in the U.S., 1965, p. 61 in the Westminster paperback edition).

The Eternity editors knew that all of the questions I was raising were sensitive and controversial. And although it was common in conservative evangelical circles to bemoan the direction that conservatives and fundamentalists believed many seminaries to be headed in their views of the Bible, the editors probably felt it unwise to mention that here. They may also have felt that their readership might not appreciate being reminded of the willingness of Pentecostal and Holiness groups to recognize women’s gifts, including preaching. I don’t know their reasons; I just know that section was cut out.

How the Article Originated

The idea for the article had originated several years before I actually wrote it. Eternity, my favorite evangelical magazine at the time because of the way it stretched minds rather than appealing mainly to hearts, had published two side by side articles in November, 1963 on the question of “women in the church.” One was a gentle essay by a Canadian minister named H.H. Kent in which he stressed the importance of recognizing the Holy Spirit’s coming upon both women and men on the Day of Pentecost (Acts 2) as a fulfillment of Joel 2:28-29. He also provided examples of women in Scripture using their leadership and prophetic gifts. I was thrilled to see his stress on women’s gifts as seen in passages that had meant so much to me ever since I had begun studying the question in my late teens.

But the other essay on women’s place in the church struck me as bombastic and misogynistic. It was written by Charles C. Ryrie, dean of the graduate school at Dallas Theological Seminary. He had already written a book titled, The Place of Women in the Church. The excerpt from his article used as a “pull quote” on the title page said in bold letters, “Ryrie says: ‘A woman may not do a man’s job in the church any more than a man can do a woman’s job in the home.’” I was incensed immediately, since I believed that men were just as capable as women to cook, care for children, and otherwise look after a household (presumably what he meant by “a woman’s job in the home”). And I believed that women were just as capable of doing any job a man could do in the church.

I kept thinking of other things I didn’t like about Ryrie’s reasoning and selective proof text approach. He said that while the Apostle Paul might have acknowledged that women were prophesying in the Corinthian church (I Cor. 11),”it does not necessarily follow that he approved of it” (italics Ryrie’s). He went on to say that when Paul really did get around to speaking his own mind on the topic in chapter 14, “he lays down a strict prohibition against women speaking at all in the church.” He said that even though Jesus told women to witness to his resurrection, Paul did not include women in his list of resurrection witnesses in I Corinthians 15. Ryrie went on to say that women were not given the gifts of preaching or teaching.

I was very angered by this article and thought about how I could answer what I felt was very biased reasoning. (I’m sure he and his followers would have said the same about mine.)

And then after the January issue came in the latter part of December with responses to the two men’s articles, I could keep quiet no longer. I went to my manual typewriter (remember those?) and began pounding away, intending to fire off a letter to the editor. It began,” Regarding Dr. Ryrie’s comments on “Women in the Church” (November) and some of the letters in the January issue, it seems difficult to believe that God is the woman-hater some of these statements imply. Apparently, there are still those who, like Christ’s disciples, marvel that He should be talking to a woman!”

The letter kept getting longer and longer, and when it hit 300 words, I knew it was far too long to be published in the brief letters-to-the-editor section. I kept crossing off parts, penciling in changes, substituting a single word for a phrase and anything else I could do to. I got to the part where I said “No one brought up the practical implications of this question. Is the Sunday School technically a part of the local church, therefore meaning a woman is not permitted to teach a mixed college-age or adult class?” I went on and on, much of it in the exact same wording that my later article used.

But because of the length of these notes, I decided to put what I had written aside and save it for a possible article—or even a book—some time in the future. I placed the one and a half scratched-up, single-spaced pages in a file folder I had labeled simply “The Woman Issue” and put it in a filing cabinet. I still have those notes, nearly half a century later.

In May, 1965, I got the notes out again and wrote “Women’s Place, Silence or Service.” In a letter to William Petersen, the executive editor, I wrote in part:

In recent conversations and periodicals, I’ve noticed that a subject of perennial interest is the subject of women—their place in society, the home, and the church. I know that you are very much aware of this interest and that Eternity has published several articles on some aspect of the subject within the past couple of years.

The articles on “Women in the Church” in the November, 1963 issue were read with great interest, since this is something to which I’ve given much thought and study. [My husband an I] have had so many people (particularly young adults and college age) ask us about this subject recently. Thinking that perhaps it deserves further exploration, I have prepared the enclosed manuscript for your consideration. I’ve attempted to approach the subject from the standpoint of practical problems and historical perspective and to raise some questions which are often avoided.”

I heard back in August, 1965. “Dear Letha, For a change, I was going to be real efficient on a Scanzoni manuscript and get an acceptance off to you before very many weeks elapsed, “ Bill Peterson wrote. “That was before I went away on vacation. . . . However, we are delighted with your handling of this subject and we want to accept it for publication in ETERNITY. . . .”

The article was then published in February, 1966, nine months after I wrote it.

In another post, I tell the story behind my second article for Eternity during the 1960s, this one on equal-partner marriage, and how it led to Nancy Hardesty’s and my meeting and coauthoring All We’re Meant to Be.